http://sharetipsinfo.comJust get registered at Sharetipsinfo and earn positive returns

With the Reserve Bank of India easing monetary policy, the theatre of action seems to have shifted to Delhi, with industry lobbies and a section of economists demanding a fiscal stimulus to boost the sagging fortunes of the economy. However, revenue constraints may limit the government’s ability to spend beyond what has already been proposed in the Budget, unless it resorts to extra-budgetary methods to boost public sector spending.

The latest data from the Controller General of Accounts (CGA) shows that the gross tax collections of the Union government in the quarter ended June grew at 1.4 percent over the year-ago period, the slowest pace since the slump following the global financial crisis in fiscal 2010. In the quarter ended June 2009, tax collections had fallen by 11.4 percent over the year-ago period. The last quarter was the worst June quarter in terms of tax collections since 2009.

The year-on-year growth rate required in the remaining part of the year (Jul-Mar) to meet the budget estimate for fiscal 2020 is now 22 percent. But even if it misses the target for the year, it does not necessarily mean that the deficit target would be missed, at least on paper. In past years as well, the government has missed revenue targets, and often made up the shortfall to a great extent by delaying payments and through off-budget financing.

However, it is worth noting that such methods are not sustainable, and over time, the government’s auditor (CAG) as well as the government’s creditors (bond markets) have become extremely wary of the government’s off-budget financing methods. They may not continue to look the other way as such accounting tricks are deployed each year to make deficit figures appear respectable. Already, speculation about a stimulus package has sent bond yields soaring (bond yields are inversely related to bond prices). If yields continue to rise, this could raise the government’s borrowing costs significantly, and negate the impact of a stimulus package.

The core challenge facing India’s public finances is its broken revenue generating system, which cannot be fixed without structural reforms. And the first item on the reform agenda must be the goods and services tax (GST).

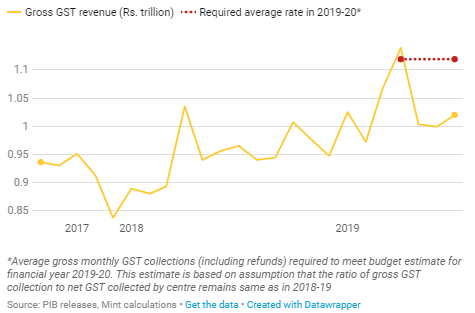

The shortfall in the centre’s GST collections was as high as 22 percent in the last fiscal year, provisional data from CGA shows. Given the trend in monthly collections so far, the prognosis for GST collections does not appear bright for fiscal 2020 as well.

Despite pick up, GST collections remained below the required monthly rate in July

Hailed as the single biggest tax reform when it was implemented in July 2017, GST was expected to boost indirect tax revenues and improve compliance even while adding to growth

After two years of botched implementation, GST has failed to live up to its promise. A recent Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) report shows how revenues have in fact slowed down after the introduction of the new tax.

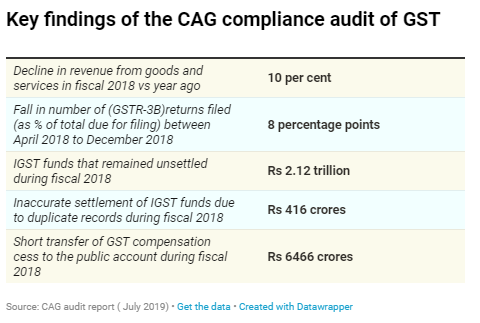

The government’s revenues from goods and services (excluding petroleum and tobacco) in fiscal 2018, the first year of GST, fell 10 percent over the year-ago period (after these goods and services were subsumed under GST), the auditor’s report showed. With this, the growth in aggregate indirect taxes slowed down to 5.8 percent in fiscal 2018 from 21.3 percent in fiscal 2017.

While economic slowdown and GST rate cuts may partly explain the lacklustre growth in indirect tax collections, according to some economists, a complex structure may have also contributed to the disappointing revenues collected under GST. In an interview to Mint, the former chief economic advisor to the finance ministry, Arvind Virmani argued that a simpler single rate structure (along with exemptions and surcharges) would have simplified the compliance process and made tracing taxable transactions easier.

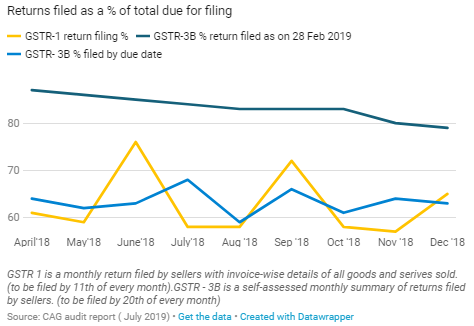

The complexity of GST returns that have to be filed by GST-payers and the technical flaws in the GSTN system has meant that tax compliance has not increased meaningfully in the post-GST era, the CAG report pointed out. The promise of a simplified tax compliance regime continues to remain elusive, it further added.

GST has not seen any significant improvement in tax compliance

The complex structure with many tax rates has made the system of input tax credit (ITC) --- the bedrock of the GST reform --- susceptible to fraud. Input tax credit is a refund businesses can claim for GST already paid on the goods and services purchased as business input. But a complicated tax rate structure with different tax rates applied to different goods and services (and in some cases different rates applied to the same product or service based on material or unit value) along with a complex set of rules has introduced several loopholes in the system.

For instance, GST rules allow real estate companies to choose between a lower rate of 5 per cent without input tax credit or a higher rate of 12 per cent but with input tax credit. Real estate companies can choose different options for different buildings (or towers) even within the same real estate complex provided they are registered separately under the Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act. As a Business Standard report pointed out earlier this year, this allowed some real estate companies to game the system and claim higher input tax credit than they were entitled to, by opting for 5 percent tax on one tower and claiming refund for GST paid on the entire construction cost by opting for 12 percent GST on other towers.

Other reports of ‘briefcase firms’ have emerged which suggest that fake companies have been floated to issue fake invoices and fraudulently claim input tax credits.

When GST was first rolled out on July 1, 2017, it was visualized along with a self-regulating system of invoice matching, which was crucial for determining the final input tax credit (ITC) in a fair and correct manner. As per the original design, input tax credit was to be generated in the GST portal after reconciling invoice-wise details from returns filed by sellers with those filed by purchasers. But even after two years, such a system-verified and automated process has not become fully functional, the CAG report noted, underlining that this system is necessary to realize the benefits of the tax reform.

“It (automated invoice matching) would protect the tax revenues of both the Centre and the States, it would lead to proper settlement of IGST (Integrated Goods and Services Tax) and would minimise, if not eliminate, the tax official-assessee interface," the report said. “In fact, even “assessment" in the sense understood in the manual system may no longer be necessary (returns themselves can be generated by a system that matches invoices); and cases of evasion etc. can be traced by applying analytical tools and AI to the massive data that crores of invoices generate."

Unsurprisingly, the current system has led to tax leakages and errors in computation of tax revenues of both the Centre and the states. But it has also led to improper settlement of the IGST (paid for inter-state transactions), the auditor pointed out.

During fiscal 2018, Rs 2.12 trillion of IGST balance was unsettled due to incomplete information in the ledgers. This reflects delays in settlement of IGST to states. Owing to the huge unsettled balance in IGST, the GST Council in its 25th meeting held in January 2018 recommended advance settlement of Rs 35,000 crores to the Centre and the States on provisional basis, which left an unsettled balance of Rs 1.77 trillion. While the IGST funds are being transferred to states on an ad-hoc basis, these transfers are provisional in nature as the GSTN system has so far not allowed a calculation of the actual transfers that need to be made.

The CAG report also highlighted that during fiscal 2018, there was a shortfall of Rs 6,466 crores in transfer of GST compensation cess (meant for transfers to states) to the public account (where the government parks funds not belonging to it). The lower transfer to the public account inaccurately bumped up the government’s fiscal position at the end of the financial year.

If indirect taxes appear to be a mess, things do not appear bright on the direct taxes front either. While there was a spurt in the growth of direct tax collections after demonetisation, it slipped in fiscal 2019 according to the provisional tax receipt figures from CGA. The average growth in direct tax collections over the past five years was 12 percent compared to an average of 15 percent under the UPA II government (2009-2014).

Reforms such as the direct tax code which could have lent simplicity and stability to the direct tax system have remained pending for long years.

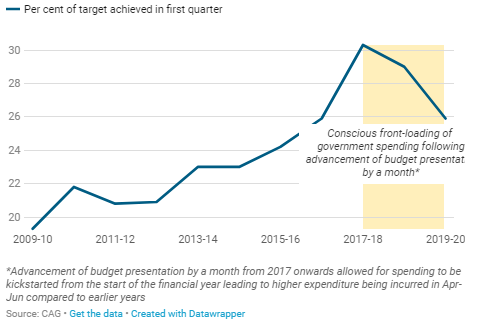

Unless the government reforms its tax structure to boost revenue collection, it will have to keep relying on off-budget funding or incur spending cuts. As a share of the budget estimate, the government’s spending in the first quarter of the current fiscal (quarter ending June) has already seen a sharp decline compared to the previous two years.

Government spent a smaller share of the annual estimated expenditure in Apr-Jun this year

As the pressure to spend rises, and the government’s revenue projections become ever harder to achieve, would we witness new forms of tax adventurism once again?